In early 1775, open warfare between the people of Massachusetts and the British Empire seemed inevitable. Citizens of the province had been stockpiling equipment, provisions, weapons, and supplies for months, and were poised to use them at a minute’s notice. The royal government found itself in an impossible situation; they had to recover or destroy these warlike supplies, secure the province, and restore order with only 4,000 men.

General Thomas Gage, the Governor of Massachusetts and commander of British forces in Boston, knew he had a limited time to act. He was under pressure from his superior, Lord Dartmouth, to take a swift and decisive action against the growing rebellion. However, Gage knew that he would first need proper intelligence to act upon. He sent two British Officers, Captain William Browne and Ensign Henry DeBerniere, to gather intelligence throughout the Massachusetts countryside while disguised as “country people.” In late February, Gage sent them to Worcester, and less than a month later, he turned his attention to another important community, Concord.

In early March, Gage had received an anonymous letter written in French that detailed the precise number and location of many pieces of artillery and supplies hidden in Concord. On the 20th, he ordered them to Concord, to “examine the road and situation of the town; and also to get what information [they] could relative to what quantity of artillery and provisions.” While seemingly straightforward, this would be a dangerous mission. Browne and DeBerniere had experienced a few close calls on their mission to Worcester, nearly being exposed and having to carefully choose who to communicate with and where to safely lodge for the night. They would face the same challenges on their journey to Concord.

The two officers took the Upper Post Road out of Boston, turning north once they reached Sudbury. As they approached Concord, the men took note of the surrounding landscape; the hills, streams, woods, and fields might all factor into a future military operation. Their arrival could not have come at a worse time, as the Concord militia had mustered for training that day, and had mounted an armed guard to watch the military supplies. Fortunately for them, a woman soon directed Brown and DeBerniere to the home of Daniel Bliss, a “friend to the government.” As they dined with Bliss, they were likely informed of the mass quantity of cannon, powder, flour, fish, salt, and rice that they later reported to Gage.

Soon after, the woman returned with tears in her eyes and was terrified. Men from the town had discovered what she had unknowingly done, and threatened to tar and feather her if she did not leave the town. They likewise threatened Bliss’s life if he remained in town the next morning. In that moment, Bliss was forced to make a life-changing decision. He had endured hostility from his neighbors for years, and realized that he was no longer safe. He soon left with Browne and DeBerniere down the Lexington road, never to return.

Ensign DeBerniere’s report to Gage produced valuable information that the General desperately needed. The lay of the land, nature of the roads, number of military supplies, and mood of the populace were enough to convince Gage that if he was to act, that Concord must be the objective.

Minute Man National Historical Park, the Town of Concord, the Wright Tavern, and the Friends of Minute Man will host a special event that commemorates this spy mission and the experiences of those involved on Saturday, March 22, 2025, at the Wright Tavern in Concord Center. Click here for more information.

Written by Thompson Dasher, a research assistant for the Robbins House and former Park Ranger at Minute Man National Historical Park. He has a B.A. in History from Gettysburg College and is currently pursuing a Master’s in American History at his alma mater.

Source: Gage, Thomas, and Henry DeBerniere. General Gage’s Instructions, of 22d February 1775. Boston: J. Gill, 1779.

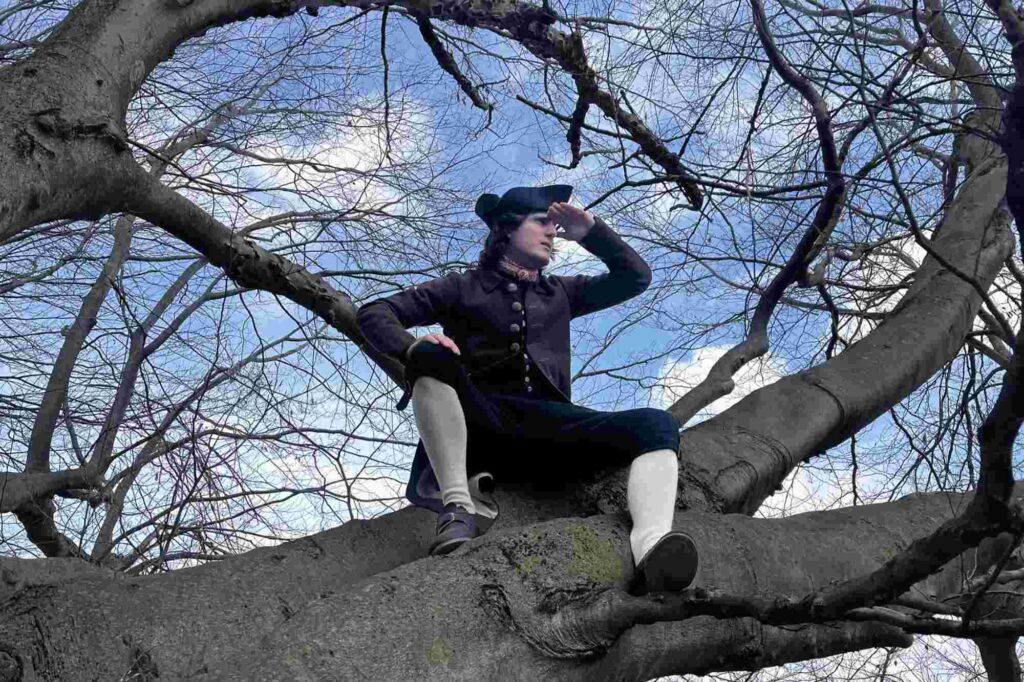

Photo courtesy of Thompson Dasher.